Despite being released on April Fools’, Immutable is no joke. Sixty-six minutes of the punishing brutality we’ve come to expect from Meshuggah can bring any man to his knees, and I barely managed to recover quickly enough to put out this review while the album is still somewhat relevant. Meshuggah is one of my favorite bands, and is undisputedly one of the most influential and unique metal bands of all time; the complexity and sophistication of Meshuggah’s compositions is next to none in the metal scene, enfeebling the noblest music theory pioneer and smiting any layman who dares to approach true understanding of the iconic Swedish quintet’s musical masterpieces. Immutable, the band says, literally asserts the unchanging nature of Meshuggah’s core style–one which has been turing eardrums into battlefields since 1987. The band’s ninth, full-length studio album, the obvious result of almost forty years of R&D from the greatest metal minds of our age, has once again raised the bar and delivered work that I can confidently say is another gleaming gem socketed in the flawless golden crown of Meshuggah’s discography.

DISCLAIMER: Meshuggah, as a band, is built on pushing the bounds of music theory and polyrhythms; therefore, any review I make of an album of theirs will undoubtedly contain exponentially more academic jargon and gobbledygook than 99% of the other reviews I write. I hope that those who don’t understand music theory will still have a good read, and that those who do understand music theory will communicate to me anything that needs correction. That being said, enjoy.

Broken Cog introduces many of the major themes of Immutable, which are obvious from the get-go: near-excessive repetition of ideas, drones, guitars tuned down to the depths of Hell, and plenty of drum-string monophony. The first idea Broken Cog throws at us is 22 eighth-notes long, which is divided into two phrases of 7 and 15. Every eighth-note has a hit except for the last two of each phrase, so rests on beats 6 and 7 for phrase one and beats 14 and 15 for phrase two. This riff lasts for about three whole minutes, which translates to approximately… a whole lot of repetitions; however, to make what I previously labelled “near-excessive” bearable, the band incorporates plenty of background ideas like drones, distant-sounding chug patterns, extended vocals, chord changes, and crash hits. Harmonically supporting rhythm-based main figures is an integral part of what I think makes a good metal song, and when I review Age by technical death metal band Aegaeon, I’ll go more in-depth into what I think layering should sound like in a genre such as this. Anyways, if the intro riff lasts three minutes and the song is about five, then what happens in the remaining ≈ 120 seconds? Well, I’ll tell you: Meshuggah comes out swinging with a relatively melodic and objectively rhythmic main riff that stands on its own just fine, but, in a move that I ferociously endorse, gets supported anyway. To support a primarily rhythm-based main figure in metal is really a must, but to support a rhythm-and-melody-based main figure in metal is going above and beyond the call of duty, and frankly I fervently hope that the band makes more of a habit out of it because Broken Cog does it so well. I can’t stress enough how much easier to listen to the guitar becomes when the light, rapid triplet, pseudo-drone riff aerates the backgrounds a few bars after the song’s second idea paves the way. The subsequent breakdown also has a supporting triplet drone, but such backup is not unexpected for a mainly rhythm-based melody. The song fades out with a return to the initial 22 beat riff and an ethereal voice uttering the phrase “voices, murmurs, whispers, purpose” repeatedly before a full stop.

The next song, The Abysmal Eye, doesn’t start quite as cryptically as the previous entry, but is none the worse for it, hosting an monophonic and rhythmic intro riff featuring the always-appreciated supporting drone to introduce what proves to be a very impressive tune. The verse riff soon swoops in, changing just enough rhythms to maintain the initial energy of the song but claim its own place in the form, while world-class drummer Tomas Haake throws us a 4/4 life preserver by hitting a stack on every quarter note upbeat. By the time the next verse rolls around, Haake replaces the upbeat hits with constant eighth-note strikes to what may still be a stack, or could very well be a hi-hat, grounding the ever-present “Meshuggah 4/4™” whether you like it or not. After the second verse, in which I forgot to mention the riff changed slightly as well, the chorus comes back, but I can’t help feeling that it’s a little different. The name of the game for this song is nuance (ironic for extreme metal, I know), and we got a taste of it earlier when the drums shifted from upbeat quarter notes to constant eighth notes; oftentimes with Meshuggah a riff can feel different even though it is the same rhythmic idea, whether because it ignores bar limits or even harmonic confines (lookin’ down at you, Do Not Look Down), so take what I say from here on out with a grain of salt. Even so, there is still undeniable nuance in this song from slight changes between verses and between choruses, the latter of which is not actually the case at about the two and a half minute mark, where The Abysmal Eye jumps into not its third chorus, but its third distinct section, the solo section. Meshuggah solos can be a mixed bag, with the really avant-garde stuff bordering on nonsense sometimes, but I’ll always approach music with the “it’s 99% subjective” attitude and thus forgive many musical ideas I disagree with. Of all the composers I can think of off the top of my head, Thelonious Monk (yes, you read that right and yes, he wore a fez) most habitually walked the avant-garde/nonsense line, but nobody debates his musical prowess and the value of his solos, so to even assert that there is such a line in music is a stretch in and of itself. This solo though? No-nonsense, without a doubt. As an ignorant drummer, I will not pretend to know how technically difficult the guitar is to play, but I’ll be damned if someone told me that the solo on this song could be composed and played by any old schmuck. The solo is succeeded by the chorus, which again I will mention has those wonderful supporting drones to go along with the badass distortion on the guitar. The ending is actually pretty traditional, and without the obvious polyrhythm element is something I could believe was from another metal band – not to say it’s bad, far from it, but being hit with something even vaguely traditional after having the “avant-garde” discussion will certainly warp one’s perception.

Light the Shortening Fuse has a very unique sounding opening that I will, to the chagrin of many, analyze. The full idea is 26 sixteenth note beats and is hard to distinctively split up into specific groups, so I’ll just explain the riff in its entirety. The initial walkdown is seven beats followed by chugs repeating along a pattern of two three-beat phrases, one two-beat phrase, three three-beat phrases, and a final two beat phrase, the totality of which which looks something like:

7+3+3+2+3+3+3+2

I think it worth mentioning that without the seven beat walkdown starting every repetition, the riff would have been really hard to identify as a single repeating pattern. I’ll keep the music theory light for the rest of the song, but that riff just caught my ear as something that required attention. The riff is not alone, however, as the oh-so-supportive drone comes back to lend a helping hand to what, despite its intense rhythmic complexity, would be an otherwise tedious section to listen to. In contrast, the verse needs no help whatsoever as its crushing brutality and ragged vocals (courtesy of singer Jens Kidman, or as I call him, Jens Oxymoron) clearly establish the brutal death metal tone that Meshuggah has dominated for over 30 years. Post-verse, the song gets a little too attached to the two and three-beat phrases I noticed in the intro, which gets somewhat stale without any supporting harmony. But suddenly, a brief instrumental interlude comes out of nowhere to save the song by throwing down some epic chord progressions and synchronised hits before filling up the spaces with, well, fills. The instrumental is my favorite part of the song, partly because it gives the tune a lot more character and distances itself from being “just another death metal chug fest,” but also because it isolates the background rhythm guitar that has been the hero of the album up to this point, giving it some well deserved recognition. The outro is a combination of the instrumental and the intro, seated on an almost ugly, concrete rhythmic foundation meagerly supported with some dirty glass drones. Overall, great intro and solid instrumental section, but the outro feels like it’s missing something and I don’t find the verses to be particularly memorable.

At around this point in the album I began to notice that Meshuggah has taken a liking to holding its listeners hostage with the intro riff before untying them with the jagged blade of supporting harmonics, but by that point the Stockholm Syndrome has set in and, all according to the band’s master plan, everyone willingly stays for the rest. This is also the case with Phantoms. As much as I would like to break the intro riff down into its rhythmic parts, I want to give love to riffs that aren’t just the first ones. Ah, to hell with it, I’ll break it down anyway…

[Two days later]

(4+7)+(3+3+3)+(4+6)+(4+7)+(4+6)+(7+6)+

(4+4)+(3+7)+(6+4)+(6+4)+(4+7)+(9+9)+

(4+6)+(7+3)+(7+4)+(7+3)+(6+4)+(6+4)

*Ahem* If you recall the beginning of this review, I mentioned how Meshuggah “enfeebles the noblest music theory pioneer”–well, with this regard, their currents turn awry and lose the name of action. When I decided to break down the first riff in Phantoms, I thought I would be getting, y’know, some cool Meshuggah ideas and a bit of intellectual stimulation. That was not the case. What I got instead was the most ******* contrived riff I’ve ever heard and a stream of grey matter leaking out of my ears and pooling onto my desk. I’m not going to pretend to like this riff. I never liked it, and after meeting it where it stood, I like it even less. But of course, the work is already done and I owe it to the brave brain cells lost in the Battle of Immutable, as well as my audience, to finish the job. Alright then, let’s make this quick. I’m counting each beat as a sixteenth note, so what’s written out as 4+7, for example, is equivalent to 11 sixteenth notes, or 11 beats. As with all Meshuggah songs, Phantoms is in 4/4, and with a sixteenth-note subdivision, a bar count of 16, and a total phrase length of 182 beats, this riff comes out to one full repetition and a remainder of 72 beats. There’s a little more to the story here with regard to how the sections deal with the riff’s incompatible bar count and how the melody interacts with the harmony, but I’ve done more than enough already so this is all you’re going to get. Humph. Enough music theory. The verse riff is a great transition from the intro all things considered: the chugs become muted, the vocals come in, and the pattern sounds simpler (but not by much). The chorus thankfully, unlike the intro, supports its riff with a background drone despite the fact that the guitar is just melodic enough to maybe not need it. It’s welcome regardless. After a return to the verse and another chorus, a new section appears, bringing (somehow) a more syncopated and jittery feel than the last few chug riffs, but momentarily it becomes clear why that is the case: it heralds the breakdown. The breakdown rectifies all the song’s past grievances, sounding like it comes straight out of DOOM, hosting an absolutely nasty chugg riff, Haake’s infallible drumming, and those distant, wailing, almost evil drones that always cemented the “welcome to Hell” feel ever-present in the aforementioned Mick Gordon soundtrack. My relationship with this song is not completely clear, but I’ll figure out how I feel about it on my own and spare you all the drama.

EDIT: I thought I’d put this here so that I didn’t interrupt the flow of the previous section, but I have recently been made aware that the riff may not be exactly what I wrote. The riff may actually one hundred and ninety-two beats, ten beats longer than my initial diagnosis. I will not change what I wrote for the following reasons: first, I’m not going back and counting out every beat to check – I’m traumatized enough. Second, because I won’t check it, I don’t know for sure if it is actually wrong. Third, if I went back and corrected the riff, it would not be my own work nor a reflection of my own musical abilities, both of which are reasons that I break down riffs to begin with. Lastly, I still feel pretty damn good about getting (maybe) within 10 beats of an almost TWO HUNDRED beat riff; that’s absolutely good enough for me and I see my failure as a kind of battle scar. All that being said, I’m obliged to insert a possibly more accurate take out there for the sake of pursuing the truth even if it discredits my own work.

FURTHER EDIT: At the behest of a reader, I’ll write the above riff out using only two’s and three’s.

(2+2+2+2+3)+(3+3+3)+(2+2+3+3)+(2+2+2+2+3)+(2+2+3+3)+(2+2+3+3+3)+

(2+2+2+2)+(3+2+2+3)+(3+3+2+2)+(3+3+2+2)+(2+2+2+2+3)+(3+3+3+3+3+3)+

(2+2+3+3)+(2+2+3)+(2+2+3+2+2)+(2+2+3+3)+(3+3+2+2)+(3+3+2+2)

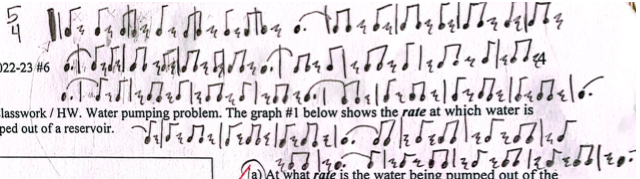

Deep and heavy is how Ligature Marks makes its entry onto the album, throwing down some of the lowest-tuned guitars I’ve ever heard, displaying yet another staple of Immutable. I am, of course, loath to ignore the well executed background drone which adds that extra bit of flair every metal riff needs now and again–a fact Meshuggah knows better than anyone. The verse also has a drone, and is the section I’ll take a deeper musical look into. I took the liberty of transcribing the verse riff during a particularly boring AP Calculus class, making Ligature Marks the first ever song to feature a Metalbum original illustration. For some reason, I wrote the riff in 5/4 instead of 4/4, so just ignore the bar lines. Anyway, the riff is just two alternating phrases: the first phrase is three 5 beat groupings of hits on 1, 3, and 5, with another 5 beat grouping of hits on just 1 and 3. The second phrase is very similar, comprised of three 5 beat groupings of hits on 1, 2, and 4, and an extra grouping with an added beat at the end.

The way I wrote it, it takes 5 full repetitions of the phrase to circle back to beat 1, but that’s also because it’s in 5/4, which is not how it’s written or played in the actual song. You’ll have to do your own math to get the real numbers on this one, but I’ve already done all the heavy lifting for you. Another riff on the board. After another verse, the third distinct section is introduced with a much groovier feel that still maintains the staccato signature of Meshuggah. However, accompanying the riff is another drone, the same one from the verse–this means that Meshuggah has come back to finish what they started in Broken Cog, that is, graciously supporting a melodic-enough main riff with a background drone. After the application of the aforementioned melodic reinforcement, the outro section takes control and me off guard. It’s a . . . strange section to hear in a Meshuggah song, to say the least, but with supporting drones vouching for it I’ll let it slide.

God He Sees In Mirrors has a very similar sounding opening to Ligature Marks, but sounds groovier and transitions into the verse much more quickly. In fact, the sections in this song rotate relatively fast by Meshuggah’s current standards, and by competent execution thereof the song benefits greatly and flows more naturally than many of the preceding entries. That also means that I’ll likely stay away from dissection this time around, as I’d really rather just focus on how the song moves and progresses aside from the math and rhythms. Case and point, the transition to the verse: after only 30 or so seconds (a blink of an eye for the band) the drums fill to a crescendo, all instruments drop out, and Kidman comes in screaming alongside Haake’s snare, crashing down like a comet. I really enjoy this part, and it reminds me of the iconic final line in Rational Gaze from 2002’s Nothing, “Never stray from the common lines,” which also throws down a mean riff afterwards; this time around, however, it’s “On the throne sits the snake.” Still as badass as it’s twenty year-old predecessor, of course. The verse also has an undeniable grooviness and unique feel to it that is quite refreshing after a long trek through a dense jungle of repetitive and hyper-complex ideas, precipitating a simple enjoyment of metal music through the absence of the overbearing polyrhythmic jittery-ness that usually permeates Meshuggah songs and demands to be understood. I needn’t fully understand this song, nor do I. What I do understand, however, is that Meshuggah certainly heard what I said about Broken Cog and responded by cracking open a crate full of drones and supporting chord progressions, which they proceed to implement in the chorus. This drone has a strange tinge to it though, almost like it’s an audio track played backwards. Needless to say, I love it. Once again, Meshuggah has outdone themselves by backing up an already groovy and melodic riff just for the sake of making a more perfect composition. Ah, Meshuggah perfectionism, what would I do without you? Anyways, the next verse, whether different from the first I cannot tell, hits just as hard as its predecessor and is succeeded by an absolutely nasty breakdown executed with technical perfection. Another verse and we arrive at the solo section. Another banger, of course, taking inspiration from its cousin on The Abysmal Eye and its ancestors from past albums to deliver the expected extreme metal solo mastery and more. God He Sees In Mirrors is a vital organ of Immutable, proving that Meshuggah still has the fast thrash-metal songwriting and musicianship that put them on the map with Chaosphere and Destroy Erase Improve decades ago. Yeah, they still got it.

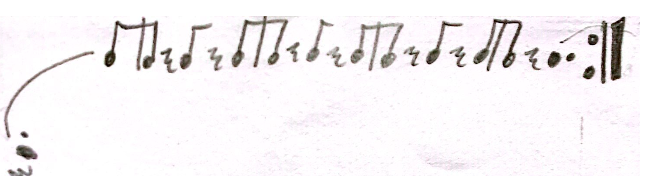

Read any of my past metal reviews and you’ll know that I love myself a good subtle intro, so it’s no wonder I’m a sucker for They Move Below with its stunningly beautiful strings and enthralling composition the likes of which I haven’t seen Meshuggah replicate so closely since Nothing‘s Acrid Plasticity. When the instrumental section ends, I’m not upset, however, but proud. Meshuggah is one of those bands who are so good, so well-entrenched in the metal scene, that they can do whatever they want with full confidence in their own songwriting and musicianship (I said something similar about STP in my review of Purple). Yet when the full force of the band comes crashing down, I don’t find myself longing for the past, but excited for what’s to come, which begins as a groovy riff and some helpful drones. The first riff lasts almost two and a half minutes(!) and serves as a framework for the other instrumentation happening alongside. The pattern of the riff itself doesn’t change much, but that which surrounds it does and makes it sound almost like three distinct sections; I can’t resist breaking this riff down, so I’ll give it to you quick. Counting in 4/4, and calling each eighth note a “beat,” the riff looks something like this:

5+2+2+2+2+1+2+1+2+2+2

Lotta two’s, I know, but that’s how I gotta type it unless I write it out on another piece of half-done math homework. The third section is the one that really got me hooked, and I’ll dissect it with pleasure (Metalbum’s first double feature–two dissections on a single song! I’m like a musical coroner, I guess). Like the intro on Light the Shortening Fuse, this riff is best looked at as one phrase. I’m going to count eighth notes here, so one eighth note = one beat. That being said, the pattern is relatively short, consisting of 23 beats; the phrasing sounds like this:

2+3+3+2+2+2+4+5.

The harmonic structure changes however, so it doesn’t end up sounding like that singular phrase repeated verbatim every time. Regardless, the rhythms of the chugs in this riff are certainly similar to others in the song, and it can thus can be presumed that most of the other guitar structures use these or similar eight note groupings to construct their riffs. Actually, with that in mind, I’m going to leave the other riffs in the song unspoken for. The solo, however, will indeed boast me as its glorious and most vociferous mouthpiece. When I first heard it, it sounded like a melody, repeating every so often, nuanced enough to be confused for a riff. Yet when it really kicked in, I was enraptured. Somehow the band managed to capture the beauty of the intro and caravan it undamaged even through the muck and mire of distortions and chugs. Unfortunately, I get flashbacks to the solo on Closed Eye Visuals (from Nothing), which, being perhaps my favorite Meshuggah solo ever, does raise the bar a tremendous degree. Despite that caveat, I enjoy the solo and am thoroughly impressed. The groove doesn’t stop after the solo though, and the remainder of the song is a masterful unification of rhythm, harmonics, and melodics that makes repetition inventive and stagnation progressive. My measly words cannot truly give justice to how much my ears are pleased by the post-solo of They Move Below, so I’ll let my lack thereof do the talking (or lack of talking).

Kaleidoscope doesn’t mess around. One snare hit, a distortion guitar, and absolutely no BS. Straight to the point, this song opens with one of the heaviest and nastiest riffs on the album. Like God He Sees In Mirrors, the riffs in Kaleidoscope seem just simple enough to be enjoyed without the temptation to delve into the rhythmic composition, something I am absolutely relieved to hear. It’s wonderful that, almost forty years in, Meshuggah can just sit down and play some metal–not to say it’s incomplex–that doesn’t rack the brain. I don’t want to spend too much time on the musicality of Kaleidoscope considering its role as a relief song (or as much as any song can be in this God-forsaken genre), but I also want to give it the credit it’s due. Thus, I have an excuse to talk about the lyrics. Meshuggah’s lyrics are written almost exclusively by drummer Tomas Haake, and as a drummer myself, I’m always glad to see a drummer-poet break the “one-trick pony” stereotype that, while often true, can prevent drummers from pursuing lyricism (which might actually be for the best, now that I think about it–I’ve heard some really dumb stuff from drummers). I’ve been a fan of Haake’s lyrics for quite some time, and always cite obZen as his best album lyrics-wise; this is primarily because all of its songs stick close enough to the overarching concept of the album for Haake to develop more complex ideas in the limited time an album format allows. However, Immutable, which I consider an album based on a musical concept more so than a lyrical one, needs each song to be written with unique enough lyrics to assert any clear poetic value, which I would say is the case with Kaleidoscope. Coincidentally and ironically, there are lyrics in the song that are quite reminiscent of those from obZen and past releases, like “this beautiful, terrifying state” reminding me of “explosions of terror and beauty” from Closed Eye Visuals and the myriad of paradoxical lyrics from the title track of obZen such as “a state of perfection immersed in filth” and “salvation found in vomit and blood.” Haake has always brought sophisticated lyricism through both interesting original thoughts and intriguing syntax modification, not to mention some im-puh-ressive vocab for a born-and-raised Swede. Musically, Kaleidoscope is a song that may not seem to have all of the brain-melting confusion of the earlier entries, but it most certainly deserves its place on this album as a hardcore, maniacal metal anthem which, like They Move Below and God He Sees In Mirrors, says more about the band through it’s straying from the usual habits than do those songs which simply execute those habits well.

The Paradoxical Spiral – er, I mean Black Cathedral, starts with some kind of guitar thing that, as a drummer, I can’t describe. Listen for yourself, and then listen to The Paradoxical Spiral from Catch Thirty-Three because it’s the same exact thing. Oh, uh, by the way, that’s the whole song too. Yeah, so, Black Cathedral is just two minutes of that thing I mentioned earlier and nothing else. Not sure I’m qualified to talk on this one, so I’m just going to move on.

EDIT: Apparently it’s called “tremolo picking.” Bully for them.

I Am That Thirst has an opening similar to Light the Shortening Fuse, with a walkdown followed by some quick alternating chugs. Alright, look, before we go any further, I’ll be honest with you all here: I didn’t break this one down. This is the only riff in the album that I display broken down without actually having done the dissection myself. All credit goes to Yogev Gabay on YouTube, who, with his Time Consuming series, has essentially become YouTube’s resident polyrhythm expert. I’ve been a huge fan of Yogev for some time now, and unfortunately allowed myself to watch his video on I Am That Thirst before I wrote this review (and therefore cannot unlearn what he taught me). Credit aside, the riff is in sixteenth-notes, so one sixteenth note = one beat; the phrasing is three groups of four sixteenth notes followed by alternating duo groups of three and two, which, when written out, looks like this:

(4+4+4)+(3+3)+(2+2)+(3+3)+(2+2)+(3+3)

Moving on, the verse riff has an awesome feel to it, hosting just enough subtle melodic content to enrich the section without taking away from the heavy metal feel; it also transitions very smoothly back to the intro riff and, later, into the chorus. Speaking of which, the chorus has one of the most well-executed drones on the album over a surprisingly quiet main rhythmic riff; it’s almost as if the riff is the one supporting the drone this time around. Most of the sections, up until the post-chorus section, have been pretty quick, so when the aforementioned section appears with a slow, almost cliché death metal riff, it certainly comes as a surprise. The last section, to Yogev’s elation, sees Meshuggah, possibly for the first time ever, switch subdivisions mid-riff – if you want to know more, go check out his video on I Am That Thirst because I can’t explain it and its significance better than he does.

The Faultless opens with an almost comically metallic riff, as punishing and as heavy as an anvil to the sternum. However, the addition of some flair makes the riff really hit home, calling in the support of another drone (almost a solo if you ask me) and a really saucy three-note tag at the end of each riff, the third installment of the latter leading into the verse. The verse changes little but makes enough space for Kidman to fill in the gaps with his classic brutal delivery. Soon enough, the next section, also hosting vocals, switches the riff even further to introduce what I would like to call the chorus. But, before we have time to fully appreciate it, we are swept up into the pre-solo section, and in no time we find ourselves drowning in the whirlpool of guitar shreddery, swinging our eardrums round and round and flinging us into one of the most unique breakdowns on the album. A heavy, palpably doom-metal and almost Black Sabbath-esque chug riff lays down a track that hosts a voice I can only describe as demonic, preaching some of what I would honestly call the most coherent and least mysterious lyrics Haake’s ever written: “Of all the wounds I expected // Heartbreak, bereavement, and despair // I never saw these coming // The gashes of your betrayal.” Whether it’s their delivery or their composition, these lyrics really hit hard and give the song ample character to precipitate enough imagery and atmosphere to flavour the rest of the tune on subsequent listens. The Faultless, like God He Sees In Mirrors, has a plethora of iconic and quickly-changing riffs that give the song a sense of pace which prevents any slowing down of the feel as a by-product of dissection; I’m not trying to excuse my lackluster analysis of the riffs themselves, but rather assert that as an individual composition, The Faultless is best left untamed.

P.S.

That three note tag at the end of the intro/chorus riff isn’t just “saucy:” it’s absolutely filthy. I’m talking covered in grease and stains, ash and dirt caking every unsaturated surface, the mere stench evoking the most primal urge to evacuate immediately or suffer unprecedented noisome disruption to the point of regurgitation. They dug that tag out of some ungodly trash heap and didn’t bother to clean it at all, perched, rotting banana peels and browning apple cores undisturbed, shards of glass from empty, broken bottles protruding from awful gashes, and scraps of ruined cloth clinging to whatever sticky surfaces remain unclogged with other refuse. Words can hardly describe the absolute FILTH and NASTINESS that such a tag has unleashed. I’m telling you, between this tag and that one muted bass line in the middle of Gojira’s Another World, I’m about ready to throw my almost paper-thin and equally undefined “keep the vulgarity to a minimum” rule out the window. It’s that gross.

Armies of the Preposterous introduces itself with (and maintains) a really solid double-bass groove on the kick drums which serves to cement it as one of the “jankier” and less flowing Meshuggah songs, in contrast to the previous entry on the album. Reminds me a lot of Swarm from Koloss (2012). This riff is actually pretty easy to understand: it’s just groups of six sixteenth notes over 4/4. “Oh, but Metalbum, that’s so lame – why don’t you break down one of the more complicated ones?” Because I’m tired. Its song number twelve, this review has taken me over two weeks, and I’m tired. You’ll get a one sentence “analysis” and you’ll like it. Anyway, this relatively simple polyrhythm backs the verse, which is also the first section of the song; no intro this time, it seems. Even into the pre-chorus the double bass continues to punish, taking breaks only to let certain distortions ring out for an extra beat before coming back, whip in hand. By the time the chorus rolls around, the feel becomes much slower, the riff becomes more sparse, and the harmonic drones change chords in time with the thereby accentuated 4/4 backbone. When the chorus returns the second time, it is accompanied by vocals and a twice-as-long bar count, providing a vague but necessary overall narrative structure for the song. The subsequent breakdown and following outro, despite having original enough feels to each, make clear the song’s emphasis on the earlier-cited double-bass-backed jitteriness; somehow the repetition and near-overreliance on this staccato texture improve the song both musically and individually instead of greying it out as a boring, monotonous piece. Meshuggah knows that repetition is not equivalent to repetitiveness, but they sure walk the hell out of that line.

Before I talk about Past Tense, I wanted to highlight the role of its cousins in their respective Meshuggah albums. These “cousins” are usually very toned-down and calm pieces usually characterised by acoustics, slow tempos, and no drums. I’ll admit that these are usually some of my favorite songs on the album, but not always. Some songs I include in this family are Acrid Plasticity from Destroy Erase Improve (1995), Obsidian from Nothing (2002), The Last Vigil from Koloss (2012), and of course Past Tense from Immutable (2022). In retrospect, some of Meshuggah’s albums actually lack such a song, and I’ll admit that they’re likely the worse for it. Each of the aforementioned albums benefits greatly from each of those songs, and there’s little I wouldn’t do to see such an entry on the likes of 2008’s obZen or 1998’s Chaosphere. With the song contextualized, I’ll go ahead and say that it is less “pretty” than Acrid Plasticity, but more so than Obsidian – it occupies a space similar to The Last Vigil, but the latter has only a single idea whereas Past Tense has a lot of development. Where The Last Vigil has one section, and Obsidian has two, Past Tense has four distinct sections – and they’re all great. An awkward and malignant section one, a sensibly developed and more digestible section two, an ominous and foreboding third section, and an “all of the above” final section give Past Tense its own original spot in the ranks of its predecessors and a deserved place as the closer on Immutable.

I can still vividly recall one day in my sophomore year of high school when my drum teacher, on the topic of my interest in polyrhythms, asked me if I had heard of Meshuggah. I said no, and he told me they did all their songs in 4/4 but… not quite; I thought that was cool and I checked out Bleed, which happened to be their top song at the time (and it probably still is). I loved it, but when I went to listen to more of their discography, I was repulsed. “I mean, I like metal, but how can anyone listen to this? It’s so loud and fustercluck-y,” I thought, but somehow I overcame my repulsion and kept coming back again and again and again and again, over and over until I had cordoned off a whole section of my brain to house my treasured memories of the distinct tastes and sounds of all of Meshuggah’s output. When Immutable came out, I knew that I would have a hard time compartmentalizing all of my past thoughts on Meshuggah, but luckily for me the album was original enough to not need shamefully constant comparison to past works. Two weeks and over five thousand words later, I’ve barely managed to scratch the surface of my love for Meshuggah, and I doubt I ever will. Ironically, however, I never recommend Meshuggah to anyone. Why? Because it’s work. It’s not some Grateful Dead-esque chill out music where you can just turn your brain off and “feel the love;” no, Meshuggah is work, especially if you want to understand it. I didn’t like Meshuggah when I first started listening to them, and I doubt many people will. But if you’re willing to put in the work, then I can’t fathom a more satisfyingly sophisticated musical endeavor than the pursuit of proper Meshuggah appreciation. Lastly, meshuggah means “crazy” in Hebrew, and I’ll tell you right now that these guys are definitely ******* crazy. Good luck.